Introduction

Upon graduation from high school in suburban Chicago, I took off for Coalwood, West Virginia and spent the summer of 1968 working on a construction job for my grandfather’s and father’s company, Case Foundation. Case had been hired by the Olga Coal Company to install a two thousand foot air shaft for a new section of Olga’s coal mines, so, basically, I spent the summer digging a hole—a very difficult and dangerous job. I’d never been to Appalachia and, in retrospect, it was a very unusual place for a preppy Chicago boy like me to go. A few days before I left, Senator Robert F. (Bobby) Kennedy was shot in the Biltmore Hotel in Los Angeles while attending a fundraiser for his campaign to become the President of the United States, just like his brother, Jack. He died the next day. Three months earlier, the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. Both of these young leaders were opposed to the Vietnam War which by that summer had reached its peak of 537,000 U.S. troops. Among them was U.S. Army First Lt. Homer “Sonny” Hickam from Coalwood, who many years later would write a memoir of growing up in that town, Rocket Boys. Over 16,000 American soldiers were killed in Vietnam in 1968. Our country’s fabric was being torn apart by the War and the Civil Rights movement. Maybe Coalwood wouldn’t be such a bad place after all to spend a few months. The top three songs that summer were Hey Jude, by the Beatles, Young Girl, by Gary Puckett and the Union Gap, and The Rascals’ Beautiful Morning.

Upon graduation from high school in suburban Chicago, I took off for Coalwood, West Virginia and spent the summer of 1968 working on a construction job for my grandfather’s and father’s company, Case Foundation. Case had been hired by the Olga Coal Company to install a two thousand foot air shaft for a new section of Olga’s coal mines, so, basically, I spent the summer digging a hole—a very difficult and dangerous job. I’d never been to Appalachia and, in retrospect, it was a very unusual place for a preppy Chicago boy like me to go. A few days before I left, Senator Robert F. (Bobby) Kennedy was shot in the Biltmore Hotel in Los Angeles while attending a fundraiser for his campaign to become the President of the United States, just like his brother, Jack. He died the next day. Three months earlier, the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. Both of these young leaders were opposed to the Vietnam War which by that summer had reached its peak of 537,000 U.S. troops. Among them was U.S. Army First Lt. Homer “Sonny” Hickam from Coalwood, who many years later would write a memoir of growing up in that town, Rocket Boys. Over 16,000 American soldiers were killed in Vietnam in 1968. Our country’s fabric was being torn apart by the War and the Civil Rights movement. Maybe Coalwood wouldn’t be such a bad place after all to spend a few months. The top three songs that summer were Hey Jude, by the Beatles, Young Girl, by Gary Puckett and the Union Gap, and The Rascals’ Beautiful Morning.

The Letter (Back Story)

By Casey Gauntt

There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy. Hamlet, Act 1, Scene 5 William Shakespeare

Monday morning, November 3, 2008, my assistant Shelley came into my office. I practice real estate law with a large corporate firm in San Diego. She had taken it upon herself to screen my calls. It had been only three months since the accident and I remained surrounded by eggshells “I just took a phone message for you from an Emily Sue Buckberry. She said you both were in Coalwood, West Virginia many years ago and she has something of yours that you left behind. She would like to return it to you. Here’s her cell phone number if you want to call her.” I took the message and thought ‘this is strange.’ I had no trouble remembering Coalwood, but there was no recollection whatsoever of an Emily Sue Buckberry and I could not imagine what I might have left behind that would prompt her to call me now, forty years later.

I spent the summer of 1968 in Coalwood, West Virginia. I was eighteen years old, a recent graduate of Lake Park High School in Medinah, Illinois, a suburb twenty miles west of Chicago, and headed that fall to the University of Southern California. Coalwood was a coal mining town of 1800 people located in the southwest corner of West Virginia and owned by the Olga Mining Company. Olga owned the entire town—the mines, the stores, the swimming pool, the miners houses, the three story boarding house known as the Clubhouse where I stayed—everything.

Case Foundation Company, a Chicago based outfit founded by my grandfather, Vernon D. Case, and run by my father, Grover Cleveland Gauntt, Jr., had been hired by Olga to install a two thousand foot ventilation shaft for a new section of Olga’s subterranean coal mines. I remember sitting at the dinner table at our house in Itasca in May of 1968 with my dad and Jim Walton. Jim was a long-time Case Foundation employee and was heading up the job in Coalwood. He had a great sense of humor and often had that look of someone who recently heard a good joke and was retelling it in his mind.

Jim and my father served together in the Army’s 145th Infantry Division during World War II, including two years in the South Pacific on the Solomon Islands and the Philippines; a.k.a. hell. If my dad had a best friend, it was probably Jim Walton. At some point during dinner Jim suggested with that signature smile “Grover, Casey should come work for me in Coalwood this summer. It’ll be a real growing up experience for him.” It was obvious to me this idea hadn’t been concocted on the spot. Now, I wasn’t a novice working construction jobs–I’d spent the past seven summers working for Case Foundation– but coal mines…West Virginia, “Where exactly is Coalwood? ” I stammered.

Sunday, June 9, 1968. Tim Bowman, my age and a local Case employee, met me at the airport in Charleston, West Virginia on Sunday June 9, 1968, and drove us the two and a half hours south to Coalwood. I arrived at the Clubhouse, met the caretakers Junior and Carol Chapin, both Olga employees, and settled into a room on the second floor. I started work the next day. The jobsite was up the road about two miles from the Clubhouse, past Snakeroot Hollow, in a place called Mudhole. Case was running three eight-hour shifts per day on the job (day, night and “hoot owl”) to make up for time lost as a result of three previous premature explosions in the shaft. The work was hard and needless to say dangerous. A crew of five men were lowered down the shaft in a big bucket (a skip) by a diesel engine powered hoist. Using hand-held air compressed drills (i.e. jackhammers) with two inch diameter diamond tipped drill bits of up to six feet in length, we drilled about sixty holes through solid rock on the floor of the fourteen foot diameter shaft and then stuffed them with sticks of dynamite. I must admit the first time I used the tamping rod to pack the sticks I nearly pissed my pants. The shift boss, a burly twenty something local called Tafon, laughed “Hey Long Ass, there ain’t nothin’ to worry about ’til you put the fuses in.” I quickly learned how to do that, too. Once the charges were set we were hauled out of the hole, our faces, helmets, head lamps, and yellow rain coats and pants covered with mud and the water that constantly seeped from the sides of the shaft and dropped on us like rain. After the “top man” gave the all clear sign, the fire master flicked the ‘Hot’ switch on the radio transmitter and yelled “FIRE IN THE HOLE!” You felt it before you heard it. The ground shuddered from deep below and then BAM! Well, actually, there were about eight to ten BAMs as the fuses were set to ignite the dynamite in a sequence of explosions. After the smoke and fumes cleared the hoist lowered the “mucker,” a hydraulic man-operated claw shovel which scooped up most of the rock. We hand shoveled (mucked-out) the rest. That was the job. Each shift would pick up where the last one left off. Drill, blow and muck. On a good day the three shifts made about ten feet.

Everyone in Coalwood knew I was the son of the “boss-man” at Case, but I got along pretty well with everybody. My previous summers working construction helped a lot I suspect. Later that summer one of Olga’s or Case’s employees, I can’t remember who, confided in me that several times during the first couple of weeks after I arrived, somebody went through my things in my room at the Clubhouse. They were checking me out and trying to figure “What is this silver spoon doing in Coalwood?” Good question.

My dad came to visit me late that summer. He spent a night at the Clubhouse and went out to the jobsite to see me at work. Before he left he said “Casey, do me a favor before you come home. Get a haircut and please don’t chew tobacco in front of your mother.” I honored both requests as I recall. I flew home on August 24 and was off to Los Angeles/USC the following week with a unique reply to “So, what did you do this summer?”

November 3, 2008. About an hour after my assistant brought me the message I returned Ms. Buckberry’s call. I’d been wondering “Does this woman know what happened? Is that why she called me?” She was on a cell phone in her car in Huntington, West Virginia. “You probably don’t remember me, but that summer in 1968 we both were staying at the Clubhouse. I was living with my mother who had an apartment on the third floor. I’m several years older than you and had long brown hair. You used to play your guitar on the Clubhouse porch and sing Gina, Sunshine of Your Love and other songs.” I fibbed “It’s beginning to come back to me- I kind of remember you.” She asked me if I’d seen the movie October Sky (1999) or read Homer Hickam’s book the Rocket Boys, his memoir of growing up in Coalwood in the late 1950s. “Oh yes, loved them both.” That was true. “I grew up a few miles from Coalwood in War, went to Big Creek High School with Homer and the other Rocket Boys and we’ve remained good friends. I worked on the movie as the dialogue consultant and taught the actors how to speak the dialect in that part of West Virginia. Homer didn’t want the viewers to think folks from Coalwood sounded like something out of the movie Deliverance.”

It was pretty clear Ms. Buckberry didn’t know what happened to us three months earlier, and she finally got around to the reason she called. “One day towards the end of that summer I heard that you were getting ready to go back home. I thought ‘ Oh gosh, I didn’t get to tell him goodbye’. As I was walking up the stairs to my mother’s apartment, I stopped at the second floor and stuck my head around the corner and looked down the hall. I saw the door to your room was open and a wastebasket filled with trash outside the door. ‘Maybe he’s still in there, cleaning out.’ So I walked down the hall to your room but it was empty. I turned to walk away thinking ‘Well shoot—I didn’t even get to tell him goodbye,’ and looked down. Laying on the floor next to the wastebasket was a letter and an empty envelope. I reached down and picked them up.”

December, 1970. After I left Coalwood, I got all caught up with college and fraternity life at USC over the next two and a half years. During this same period Case Foundation and my father were consumed with financial problems. The economy was in a deep recession, Case owed its banks a lot of money and the developer of Chicago’s then tallest building had filed a $160 million lawsuit against Case and my dad alleging faulty foundation work. My father desperately tried to resolve these problems so he could get out of the construction business and focus on his new career as a commodities trader. But that, too, went south. He became more and more frustrated, exhausted and depressed.

I flew home to Itasca for the Christmas holidays on December 21, 1970, the day before my dad was to return from a business trip. I awoke about ten o’clock the next morning. My thirteen year old sister, Laura, had crawled into bed with me. She was shaking, crying. My mother stood in the doorway, her face ashen, an unfiltered Chesterfield dangling between her long, well-manicured fingers. “They found your dad in his office this morning. He’s dead. The police say he shot himself.”

A friend drove me to O’Hare Airport later that afternoon to pick up my older brother, also named Grover, returning from the Wharton School in Philadelphia. I broke the news to him standing on the curb in front of baggage claim.

December 24, 1970. On Christmas Eve day a Case Foundation envelope arrived, addressed to me and postmarked December 21. Inside was a handwritten note scrawled by my father and three one hundred dollar bills. “Please get something for your mother and Laura for Christmas.” One line. I gave the cash to my mother and tossed the letter in the trash. Two weeks later my mother packed up the house and she and my sister moved to California to live with her folks.

I graduated from USC in 1972 and continued on and received a law degree in 1975. I married my angel, Hilary Tedrow, in August of 1973. We met four months after my father died. She is the most beautiful woman I know. In 1970 she was crowned USC’s Miss Helen of Troy. Imagine high school prom queen and homecoming queen combined and multiply that by a hundred. And as far as her beauty inside, multiply by another thousand. I practiced business law in Los Angeles for five years and in 1979 we moved to Solana Beach, twenty miles north of downtown San Diego.

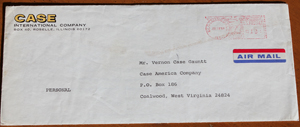

November 3, 2008. Emily continued with her story “I saw it was a Case Foundation Company envelope and it was marked Personal. I scanned the first couple paragraphs of the letter real quick. It was a letter from your father. He was writing about Jim Walton, problems Case was having on its job for Olga, and I thought, ‘W-a-a-i- t a minute…. Casey shouldn’t have left a business letter like that. Anything personal in a company town…he shoulda ripped it up or something.’ You were only 18-what did you know about a company town? I figured I’ll hang on to this until he gets back to school. I’ll get his address from an Olga Company secretary I know and send it to you with a note “Casey- did you really mean to throw this away?” Well, I got busy and headed off to graduate school. I came across the letter again a couple of years later and thought ‘Oh that’s the letter to Casey. Well, I’m just going to hang onto this a little while longer, I’ll be able to find him. I kept moving around and for the last fifteen years your letter was in a box on a shelf in my mother’s garage in Lewisburg. I recently bought a house in Huntington and brought over the things I was storing at my mother’s including that box. Anyway, I’m going through my things in the boxes and there’s the letter in its envelope.

November 3, 2008. Emily continued with her story “I saw it was a Case Foundation Company envelope and it was marked Personal. I scanned the first couple paragraphs of the letter real quick. It was a letter from your father. He was writing about Jim Walton, problems Case was having on its job for Olga, and I thought, ‘W-a-a-i- t a minute…. Casey shouldn’t have left a business letter like that. Anything personal in a company town…he shoulda ripped it up or something.’ You were only 18-what did you know about a company town? I figured I’ll hang on to this until he gets back to school. I’ll get his address from an Olga Company secretary I know and send it to you with a note “Casey- did you really mean to throw this away?” Well, I got busy and headed off to graduate school. I came across the letter again a couple of years later and thought ‘Oh that’s the letter to Casey. Well, I’m just going to hang onto this a little while longer, I’ll be able to find him. I kept moving around and for the last fifteen years your letter was in a box on a shelf in my mother’s garage in Lewisburg. I recently bought a house in Huntington and brought over the things I was storing at my mother’s including that box. Anyway, I’m going through my things in the boxes and there’s the letter in its envelope.

Well, by now Google had come along and I figured I bet I can find you. So, this morning I Googled you and found a link to your law firm. I thought “Oh, he’s an attorney.’ I always figured you were going places and would be successful. I pulled up your firm’s website and there you were- your little picture-and I thought “Casey Gauntt!!! I’d know you anywhere” And so right that minute, I picked up the phone and called the number of your firm’s San Diego office and got a hold of your assistant. And here we are.” Yes we were.

Well, by now Google had come along and I figured I bet I can find you. So, this morning I Googled you and found a link to your law firm. I thought “Oh, he’s an attorney.’ I always figured you were going places and would be successful. I pulled up your firm’s website and there you were- your little picture-and I thought “Casey Gauntt!!! I’d know you anywhere” And so right that minute, I picked up the phone and called the number of your firm’s San Diego office and got a hold of your assistant. And here we are.” Yes we were.

Emily then asked me “Is your father alive?” “No, he passed away many years ago.” I shared no other details with her on this call. As soon as she asked about my dad, I already knew her next question. “So, do you have kids?” “Yes we do. We have a daughter, Brittany, twenty-eight, who was married last year and lives nearby in Del Mar with her husband, Ryan.” I paused a few seconds and pondered what I would say next. “And Emily I don’t know quite how to tell you this, but we also had a son, Jimmy….. Three months ago in early August he came home from Los Angeles for a visit. He went out with some of his friends from high school, had a few too many beers and decided to walk home instead of drive. He was struck by an automobile a few miles from our house and instantly killed. He was twenty four years old.” She drew in a quick breath and all levity was drained from her voice when she exclaimed “Oh my God!”

We talked a little more, I gave her our home address and she said she would put the letter in the mail the next day. After I hung up the phone my entire body erupted with goose bumps and I sobbed for several minutes. I’d never before experienced anything like what was now coursing through my body and I can’t even begin to describe it. I didn’t tell Emily I’d been thinking a lot about my father the last several weeks.

November 8, 2008. Hilary and I spent the day at Del Mar Beach with Brittany, Ryan and my mother Barbara. Saturday was one of those perfect days—temperatures in the high seventies, cloudless sky and the ocean at its deepest and darkest blue, almost black, all produced by the hot, dry, winds called Santa Anas that blow in from the inland deserts a few glorious days each year. Around 3 p.m. I took my mother back to her house in nearby Encinitas and, before heading back to the beach, I swung by our house and checked the mail box. Inside was a Priority Mail envelope from Emily S. Buckberry. Although I was consumed with anticipation, I put the envelope on a counter and fiddled around in the kitchen for several minutes. I don’t know why. Finally, I sat down at the kitchen table and opened the envelope. Inside was a handwritten note from Emily expressing her sadness for the loss of our son. “Here are some words from your dad, which I have miraculously held onto for 40 years, that might help sustain you as a bereaved father. It surely can’t do anything but comfort you to, once again, be reminded how much you were loved as a son.” She also enclosed a recent picture of herself to help me remember her. It didn’t.

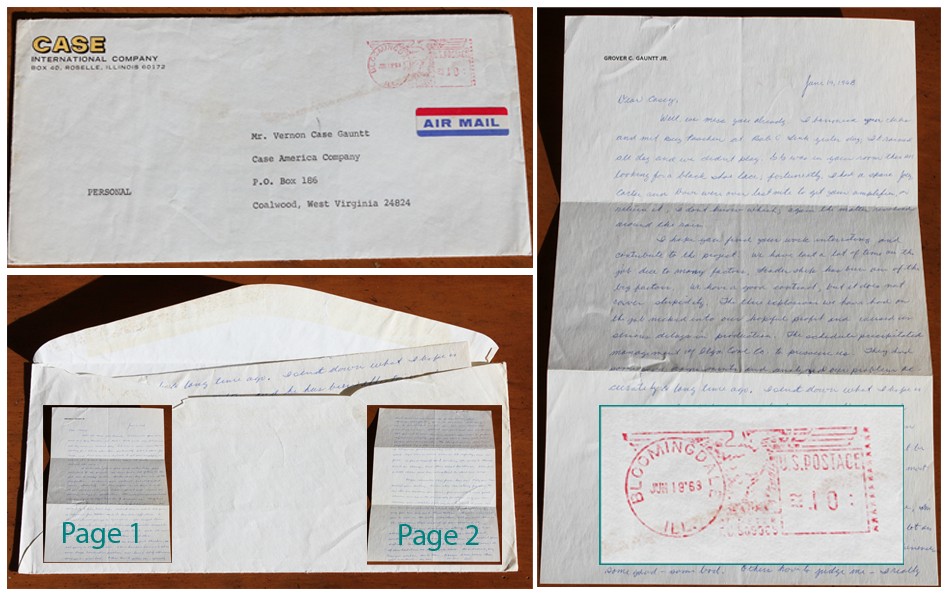

Enclosed in Emily’s package was the Case Foundation Company envelope mailed from the Bloomingdale, Illinois post office, postmarked June 19, 1968 and addressed to me, Mr. Vernon Case Gauntt, care of Case Foundation Company’s P.O. Box in Coalwood. The envelope was in perfect confition–no rips or tears–almost as if it had been steamed open. Inside was the original letter from my father, neatly handwritten with a blue pen on both sides of one page of his personal stationery. The letter was sent ten days after I arrived in Coalwood.

The Letter

Grover C.Gauntt,Jr June 19,1968

Dear Casey,

Well, we miss you already. I borrowed your clubs and met Buz Paschen at Bob O’ Link yesterday. It rained all day and we didn’t play. GG was in your room this AM looking for a black shoelace; fortunately, I had a spare. Joey, Carter and Dave were over last nite to get your amplifier, or return it, I don’t know which; again the matter revolved around the rain.

I hope you find your work interesting and contribute to the project. We have lost a lot of time on the job due to many factors. Leadership has been one of the big factors. We have a good contract, but it does not cover stupidity. The three explosions we have had on the job nicked into our hopeful profit and caused us serious delays in production. The schedule precipitated management of Olga Coal Co. to pressure us. They had some good arguments and analyzed our problem accurately a long time ago. I sent down what I hope is a reformed Jim Walton and he has been effective. I thought it well you go to Coalwood- you might learn from a bad situation. Your leadership qualities might be contagious. Don’t ever throw in the towel- make the most of a bad situation- don’t join them-beat them.

I don’t consider myself as successful, therefore, I’m not going to preach to you. I have knocked around a lot on some tough construction problems and have a lot of experience some good—some bad. Others have to judge me- I really don’t know if my reasoning, judgement and decision making are good or sound. I do want you to know that we love you and will never turn our back on you. Should you want and ask my advice, I’ll give it to you, however, I don’t expect you to follow my advice blindly, for you are now a man and must follow your own route. My thought process has been prejudiced by a depression in my youth and insecurity, by a religious fanatical mother who I could not reason with, by a war in which I was in the infantry, and so forth. I find myself not wanting the world to change, but I see change, and there must be change. I also feel a little older and am reluctant to start new ways.

Please remember this from hereon: Only you can control your destiny. No one else can study for you. No one else can discipline your mind; force yourself to read good literature and leave the pornography for others; only you can exercise your athletic body regularly so you feel good; only you can force yourself to think and reason honestly; only you can say no to temptation. The world will want you to roll in the gutter with them, but you will have in the long run their respect if you demand it.

I hope you develop a strong character to go along with your fine mind, handsome looks and wonderful body. From now on, only you can control your destiny. Give some thought to what you want to become & do. If your ambitions are high-go to work. I’ll be around, any time you want me, I’ll be there- because I care more than you’ll ever know-my son. All love. Dad.

When I finished reading the letter the goose bumps returned and my entire body was shaking as I erupted in tears. I turned around in my chair to look for him—them. I read the letter again, this time more slowly. I had absolutely no memory of ever reading it or pitching it. As with the first read, I was overwhelmed by his closing words:

“I’ll be around, any time you want me, I’ll be there— because I care more than you’ll ever know—my son. All love, Dad”

Promise Kept and Delivered

40 Years, 4 Months, 20 Days Later

My father had indeed kept his promise to me. He knew that day would be one of the hardest days of my life. You see, that Saturday, November 8, 2008, was Jimmy’s birthday. The letter from my father arrived on our son’s 25th birthday and he was there for me, as he had promised.

Amazing story.

Serendipity when it’s most needed…